Nanodiamonds are a class of carbon-based nanoparticles that are rapidly gaining attention, particularly for biomedical applications, i.e., as drug carriers, for bioimaging, or as implant coatings. Nanodiamonds have generally been considered biocompatible with a broad variety of eukaryotic cells. We show that, depending on their surface composition, nanodiamonds kill Gram-positive and -negative bacteria rapidly and efficiently. We investigated six different types of nanodiamonds exhibiting diverse oxygen-containing surface groups that were created using standard pretreatment methods for forming nanodiamond dispersions. Our experiments suggest that the antibacterial activity of nanodiamond is linked to the presence of partially oxidized and negatively charged surfaces, specifically those containing acid anhydride groups. Furthermore, proteins were found to control the bactericidal properties of nanodiamonds by covering these surface groups, which explains the previously reported biocompatibility of nanodiamonds. Our findings describe the discovery of an exciting property of partially oxidized nanodiamonds as a potent antibacterial agent.

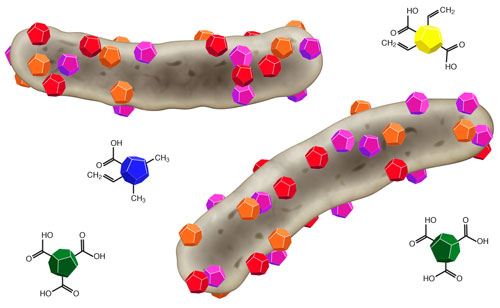

The colored particles display different types of nanodiamonds that bind to bacterial cells (grey) and kill them. (Image: University of Bremen)

Exhibiting a diameter of 5 nanometers, nanodiamonds are 200-times smaller than a bacterium. Nanodiamonds are produced by the explosion of carbon-containing compounds in high-pressure storage tanks. Here, the tiny detonation diamonds are formed besides large amounts of soot. The material scientists Dr. Michael Maas, Julia Wehling and Professor Kurosch Rezwan from the University of Bremen (Germany) have now identified the strong antibacterial properties of these nanodiamonds. Besides silver and copper, nanodiamonds might be used as a new effective agent against bacterial contaminations and infections

Discovered in the 1960s by Russian scientists, nanodiamonds only recently came into the spotlight, caused by current breakthroughs in processing and pretreatments that enabled their use in laboratories. Heat treatment of the grayish brown diamond powder can be used to generate different chemical groups on the nanodiamond surface. Biologist Julia Wehling and chemist and project leader Dr. Michael Maas discovered that some types of nanodiamonds kill bacterial cells rapidly and efficiently. Seeking to understand the reason for the antibacterial properties, both material scientists from the Advanced Ceramics Group of Prof. Dr.-Ing. Kurosch Rezwan puzzled out the cause: some oxygen-containing groups on the surface of nanodiamonds, such as acid anhydrides, seem to be responsible for the antibacterial effect of the diamonds.“The discovery that nanodiamonds kill bacterial cells as effectively as silver, which has been already used for 7000 years, opens a multitude of possible applications in biomedicine and material science. Furthermore, the concentrations that we used are proven to be nontoxic for human cells. This enables the use of nanodiamonds for surface coatings or as additives for disinfectants. In the era of antibiotic resistances, the discovery of a new antibacterial material can be seen as a breakthrough”, says Julia Wehling.The only scarcely explored diamonds were brought to the attention of Dr. Michael Maas by Prof. Richard N. Zare during a visit at Stanford University in California. “After my return, we directly started using nanodiamonds in the different nanosystems that we are working with in Bremen. We were quite surprised by how efficiently nanodiamonds killed bacteria and we are convinced that our discovery will be of great impact for further research. It can be expected that nanodiamonds will play a key role in different areas dealing with bacterial infection. Our next goal is to equip implant materials with nanodiamonds to provide them with antibacterial properties. At the same time, we want to further analyze the diamond surface”, Michael Maas says.

Source: University of Bremen

No comments:

Post a Comment